-

Dilbert’s Estimation The Purpose of Planning

Before talking about the Cone of Uncertainty and estimation lets clarify some things about planning. I constantly tell my friends and co-workers that ideas are not the same as planning. Remember the last time you started something that, for several reasons, you never ended, or that time you said my “plans” are …, but in reality, you never took real actions to execute those “plans” or you just keep putting them off. The main difference between ideas and plans is basically that ideas are vague, aspirational, and desirable; while true planning takes ideas further and establishes goals along with preconceived steps to take that eventually help to estimate, make decisions, and even refine or change the plan.

In the same way that it happens in life, in the software and IT industry in general, estimations and planning are of the utmost importance for the success of any project. The plans are a guide that tells us where to invest our time, money, and effort. If we estimate that project will take us a month to complete and in return, it will generate a million dollars, then we may decide to carry out that project. However, if the same project generates that million dollars in 15 years, then perhaps it is better to reject it. Plans help us to think ahead and know if we are progressing as expected among other things. Without plans, we are exposed to any number of problems.

In my experience as a developer, scrum master, project manager, etc., teams tend to two extremes: They don’t make any plans at all or they try so hard on a plan that they convince themselves that the plan is actually correct. Those who do not plan simply cannot answer the most basic questions, like, when do they finish? or, will it be ready before the end of the year? Those who plan too much, invest so much time in their plan that they fall into assumptions that they cannot confirm, their insecurity grows more and they begin to believe that even by planning more they will achieve more accurate estimations although this does not actually happen. If you feel identified with any of the previous scenarios, in your favor I can say that planning is not easy.

But that plans fail and planning is complicated is not news. At the beginning of a project, many things can be unknown, such as the specific details of the requirements, the nature of the technology, details of the solution, the project plan itself, team members, business context among many other things. But then, how do we deal with these riddles? How do we deal with uncertainty?

The Cone

These questions represent a problem that is already quite old. In 1981, Barry Boehm drew what Steve McConnell later called the Cone of Uncertainty in 1998. The cone shows that in a sequential or “cascade” project that is in the feasibility stage, we will normally give an estimate that is far from reality, in a range of between 25% and 400%. This is for example, that a 40-week project will take between 10 and 160 weeks. By the time we finish obtaining requirements, our estimate will still be between 33% and 50% out of date. At this point, our 40-week project will take between 27 and 60 weeks. Imagine what happens with those projects that are never clear about their requirements.

How to deal with the Cone of Uncertainty?

Buffering (margin of error)

This is to use a percentage of time and/or resources to cushion the effect of materializing risks. You have to be careful, a common reaction is to put double or triple the time to estimate a project, this is NOT buffering, this is “padding” which IS NOT a good practice. Giving a too large number will cause sponsors or clients to resist and not approve your project. Give them a too low number and you will take the risk of running out of time and money. This becomes doubly risky when you are using fixed contracts for your proposal, where there is even more pressure to keep costs down.

It is important that you make use of historical data to compare your current project with other completed projects and obtain reasonable and justifiable numbers in order to get a margin of error or buffering. Include postmortem processes or lessons learned at the end of each project to support your buffering figures in the future.

Estimate in ranges

Something I like about agile approaches for project management is being honest from the beginning and never use closed figures, but be transparent and always use ranges, especially in projects that seek to innovate and try new things where there is a lot of uncertainty. This is for example:

Look. We don’t know how long this is going to take, however, the following is our best bet based on the information we have so far. But if we can do a couple of iterations, we can develop something, evaluate how long it takes, and then have a much better idea of how big this is.

Also, present the best estimate at the moment as a range. This can help project sponsors to decide how much risk they are willing to accept.

Relative estimation

There have been various investigations on how to make estimates of effort and it has been discovered that people are good at estimating the size of something comparing it with a reference (Software Development_Effort Estimation). For example, someone cannot tell you how high the building you live in is, but they can tell you that it is approximately twice the height of the other. You can apply this principle to projects too.

Note. Agile approaches use interesting concepts like Story Points and Ideal Days to make relative estimates.

This is not a foolproof measure, you can still misjudge. But it is certainly good to get initial funding that allows the team to build something and see how long it takes to complete this progress, while simultaneously they learn more about what needs to be achieved, in such a way that this experience is used to reduce the variance of that estimated starting number.

Why is all this happening?

There is no doubt that there is always pressure from the financial sector of organizations to make estimates for an entire project or for a whole year, although these practices ultimately backfire 😀

The best thing to do is to permeate this knowledge in your organization, and constantly remind and communicate that the goal of estimating is not to guess the future, but to determine whether the project goals are realistic or even possible.

Some interesting links:

Part of the list of topics for this post and the idea of the graphic with the little sun 🙂 were partially based on articles from agilenutshell.com

These are some recommended books to know more:

Emmanuel Herrera

IT professional with several years of experience in management and systems development with different goals within public and private sectors.

Emmanuel worked through development and management layers, transitioning from developer and team development leader to Project Manager, Project Coordinator, and eventually to Scrum Master, Product Owner, and Agile Coach.

Some certifications include: PSM, PSPO, SSM.

No CommentAdministración / Management / Administración de Proyectos / Project Management / Agile / Destacadas / Featured / Scrum

Size matters?

This is a very old question, but in this blog, we only will answer that question from the project management point of view (disappointed people please go to another kind of blogs). This time we will see what are and what is the purpose of the famous User Stories and how they differ from traditional requirements in a project.

When I was a kid I spent a lot of time playing on the beach with my cousins, and in some of those games, I found myself digging, transporting and piling sand from one point to another (my tools were a shovel and a plastic bucket) after about 10 minutes my youngest cousin asked me how long it had taken me to gather all that sand, to which I replied: “about 30 laps”. After that, both my cousin and I assumed that with his own bucket he could double the amount of sand, doubled in another 30 laps. It wasn’t like that, it took a lot longer for my little cousin because we both failed to evaluate the capacity of his bucket and appreciating that Gabriel (my cousin) being very young (maybe 6 years old) he still had to strain to load a bucket of different size completely filled and finish in only 30 laps.

As simple and obvious as this anecdote may seem, the reality is surprising, since many work teams responsible for projects of all sizes continue to fall into this same error. They are not yet fully aware of their capacity or speed, nor are they clear about the difference between size and distance in a project, and therefore, they fail from the beginning in their estimates.

Not taking care of trying to measure the size of what you are going to do is an error, therefore the size does matter, and before measuring times and distances you should know the answer to questions like, what is the size of your bucket and shovel? How many buckets and shovels do you have? Are there enough people for each shovel and bucket?

What are the User Stories?

For ease, the concept is often oversimplified, saying that User Stories are the requirements of a system or a product, but they have serious differences with other common approaches such as use cases, IEEE 830 software requirements specifications, and design and interaction scenarios.

User stories are short, simple descriptions of a feature told from the perspective of the person who wants the new functionality, usually a user or customer of the product that they want to create. In general, they follow a simple template:

As <user type>, I want <some goal> so that <some reason>.

User stories are often written on chips or sticky notes, stored in a box and organized on walls, boards or tables to facilitate planning and discussion. As such, they strongly change the approach of writing about characteristics, to discussing them. In fact, these discussions are more important than any text that is written.

This is a simple definition about what a User Story is, but believe me, there is much more behind, writing good User Stories can be a challenge, and to create good stories you have to understand more about their purpose.

Assign Value (points) to User Stories

Eventually, when I became involved in project management and later Agile, I discovered that one way to estimate the size of what is needed is to use the User Stories. To explain what they are I will continue using the analogies.

When was the last time you went to a restaurant and ordered a soup or a drink in milliliters? … That’s right, we usually don’t do that, we usually order a soup or a drink with a relative measure like “small, medium or large”. User stories are also relative, they are used to express size, they don’t have a standardized value, but the values must be relative to each other, that is, a User Story that has value 2 is twice the size of one User Story that it’s worth 1.

To assign values or points to different sizes there are those who use shirt sizes, dog breeds, Fibonacci values (my favorite values) or other representations, no matter what you prefer, you should eventually use relative values. Take the following table as an example, with a possible assignment of points:

Tamaño Camisa Puntos XS 1 S 2 M 3 L 5 XL 8 XLL 12 In an Agile project, it is not uncommon to start an iteration with requirements that are NOT fully specified, the details will be discovered later during the iteration. However, we must associate an estimate with each story that we can see at the moment, even those that are not completely defined.

And where are the details?

Those used to the detail added in advance into traditional requirements will immediately come up with this question. The detail can be added to User Stories in two ways:

- Dividing a User Story into multiple User Stories and smaller ones.

- Adding “conditions of satisfaction”.

When a relatively large story is divided into Agile and multiple User Stories, it’s normal to assume that details have been added. After all, more has been written.

Conditions of Satisfaction are simply high-level acceptance tests that must be met after the User Story is completed. Consider the following as another example of an Agile User Story:

As a marketing director, I want to select a period of time so that I can review the past performance of advertising campaigns in that period.

The detail could be added to this User Story example by adding the following satisfaction conditions:

- Make sure it works with the data of the main retailers: Oxxo, Seven Eleven, Extra.

- It must support the data for the last three years.

- The periods are chosen in intervals of months (not days, nor weeks).

Who writes User Stories?

Anyone can write User Stories. However, it is the responsibility of the product owner to ensure that there is an accumulated backlog of Agile User Story products, but that does not necessarily mean that the owner of the product is the one who writes them. In the course of a good Agile project, you must have examples of User Story written by each member of the team.

Also, keep in mind that who writes a User Story is much less important than who is involved in the discussions of it.

When are User Stories written?

The User Stories are written throughout an Agile project. Overall, a story writing workshop is held near the start of the Agile project, each release and/or at the beginning of each iteration (I personally take some of the first options, depending on the length of the project, and I only do refinement in each iteration). Everyone on the team participates with the goal of creating an “order list” or Product Backlog that fully describes the functionality that will be added during the course of the project, or in a release cycle of three to six months.

Some of these Agile User Stories will undoubtedly be Epics (are not called Epics because they are dramatic…well sometimes 😄). Epics are very large stories that by their size will later decompose into smaller stories that fit more easily into a single iteration. In addition, new stories can be written and added to the “order list” of the product at any time and by anyone.

Velocity

I will not delve too much into this topic because it gives to write another post dedicated entirely to it, but to understand how estimation can work with Story Points that we assign in the table we showed above, it’s necessary to introduce a new concept: Velocity. Velocity is a measure of a team’s progress rate. It’s calculated by adding the number of Story Points assigned to each User Story that the team completed during the iteration.

If the team completes three stories, each estimated at five story points, its velocity is fifteen. If the team completes two stories of five points, its velocity is ten.

If a team completed ten points of work the last iteration, our best calculation is that this iteration will complete ten points. Because the story points are estimates of relative size, this will be true whether they work on two five-point stories or five two-point stories.

As can you see, in order to make estimations, and after knowing the sizes It’s very important to calculate an estimate for the end of the project, or for a release (the distance).

Do User Stories replace a requirements document?

Agile projects, especially Scrum projects, use a product backlog, which is a prioritized list of functionalities that will be developed in a product or service. Although product backlog items may be what the team wants, User Stories have emerged as the best and most popular form of product backlog items.

While a product backlog can be considered as a replacement for the requirements document of a traditional project and perhaps even a WBS, it’s important to remember that the written part of an Agile User Story (“As a user, I want …” ) is incomplete until the discussions about that story take place.

It’s often better to think of the written part as an indicator of the actual requirement. User Stories can point to a diagram that represents a workflow, a spreadsheet that shows how to perform a calculation or any other artifact that the Product Owner or team wants.

Until here I leave the User Stories topic, for now, let me know if you want to know more 😉.

Links of interest:

Without users (User Proxies)

The Agile Team Approach

What Scrum Master Certification to Choose?These are some recommended books to learn more:

Emmanuel Herrera

IT professional with several years of experience in management and systems development with different goals within public and private sectors.

Emmanuel worked through development and management layers, transitioning from developer and team development leader to Project Manager, Project Coordinator, and eventually to Scrum Master, Product Owner, and Agile Coach.

Some certifications include: PSM, PSPO, SSM.

No CommentAdministración / Management / Administración de Proyectos / Project Management / Agile / Destacadas / Featured / ScrumMuch has been said about the Scrum team size or Agile team size, almost every client, boss, and collaborator with whom I have worked asks this question at some point: how many people do we include in the teams? The Scrum Guide sheds very little light on this, suggesting 10 or fewer members per team in its latest update, but giving us no context or reasons for these numbers.

The Scrum Team Size is More Than a Number

The truth is that there is no universally correct number of members to ensure optimal performance in a team, but what we know is that a Scrum team must consider certain factors that should include, beyond numbers:

- Cross-Functional team. Sufficient skills and capabilities to build the product,

- Dedicated team members. Dedicated members to one, and only one, team,

- Consistent membership. Stable and long-term membership within the team[1],

- Diversity of thought. A reasonable wide range of attitudes, beliefs, genders, and thinking patterns[2].

Now, the above points already represent a challenge for some organizations, but at least they enjoy an important consensus, however, they are not the only ones. Once the team is formed, there are other important factors that high-performance teams must address, among others:

- Psychological safety. A safe environment to share ideas and take risks[3].

- Equal communication. The most expressive member should not communicate more than twice as much information as the quietest[4].

- An open mind and willingness to learn[5].

- Shared vision. Everyone knows and agrees on objectives[6].

- Clear roles. Everyone knows their responsibilities and the expectations of their work[7].

- External advice (coaching). In Scrum, this is done by the Scrum Master[8].

And what does all this have to do with the size of the teams? Well, these factors don’t live isolated in a vacuum and just because I say so, so let’s explore the evidence so that together we discover what matters most to your team. After all, there is no universal answer 🙂

Many Numbers Everywhere

When we talk about the size of the teams within various organizations, the topic seems much more controversial and narrow to say the least. In the worst cases, staffing leaders respond by building teams guided by assumptions and even based on the burden caused by unrealistic dates and budgets and inadequate time horizons, thus harming the performance of teams and the organization itself in the medium and long term.

In the early days of Agile, the XP and Scrum texts suggested that the optimal size of members was 7 ± 2, applying George A. Miller’s number, later it was adjusted to 6 ± 3, today the suggested number is 10 or less according to the Scrum Guide.

The original support for the position of seven people, plus or minus two (7±2), comes from a well-known psychology study by research psychologist George A. Miller published in the 1950s, where according to the results of this study, there are limits on the amount of information we can process and retain in our heads.

More recently in 2010, Nelson Cowan claimed that Miller was too ambitious and that the ideal limit was only four and not seven[9].

Also, Ikujiro Nonaka and Hirotaka Takeuchi were formulating the ideal team size after conducting research and creating new products at technology companies such as Fuji-Xerox, Canon, Honda, Epson, Brother, 3M, and Hewlett-Packard[10].

Many others cite historical examples dating back to the Roman army, which used small military units of around 8 people. Others watch bonobos, one of the closest genetic relatives to humans, often splitting into groups of 6-7 to forage for a day. Both conveniently support the number 7±2, but since neither example is about teams doing knowledge work, the relevance of this to agility is limited.

As you can see, the topic has been discussed for some time and can be somewhat confusing, but thanks to this we have some clues, but it is worth having more sources to help us support our decision.

What Happens to Relationships When Teams Grow?

Within a team, each individual will have a connection with another individual, thereby creating a unique relationship; the bigger the team, the more the relationships. The equation that describes this is N(N-1)/2; but what does this mean? and how can it help us? To find out, let’s remember math problems from school and turn it into something we can use in real life.

The above equation tells us how many different relationships will exist within a team of a certain size, where N = the number of people in the team. So, in the first example graph of a team of 5 people, where N=5 we have 10 relationships: 10 different combinations of team members who are related to other members of the same team.

In the second example, where N=7, you have 21 relationships, and where N=9 in the third graph you have 36 relationships. Each pair of people represents a relationship, and that relationship defines how they collaborate. High-performance teams, by their nature, must have strong relationships between each of the team members in order to collaborate effectively.

Knowing this is important for you and your team because it’s true that each new person adds some individual productivity to the team, but it also increases communication overhead in the form of an exponentially growing number of relationships. To grow a team from 5 to 7 people, you need to more than double the number of relationships. To go from 7 to 9, it doesn’t quite double, but the jump is still big.

How expensive is it to maintain these relationships? Anecdotally, after studying the interactions of the members of several of my teams, I can say that in teams of 7 or 8 people, each day more than 90 minutes per person are spent interacting with other team members[11]. This excludes time spent on techniques like pair programming. Part of the interaction is talking about work, but she also spends time socializing. This is good and important because it is the combination of work and socializing that builds resilience and the ability of a team to handle challenges effectively.

A general rule of thumb suggests that people typically have 3½ to 5 hours of productive time at work each day. As a team grows, we lose productivity or, more often, begin to withdraw socially rather than sacrifice productive time to interact with our peers because communication costs for each team member are becoming too high. We need strong relationships to become a high-performing team, but as the size of the group grows, we begin to avoid the interactions that build those relationships.

Therefore, the number of relationships between team members and the time investment they require should be a factor when choosing team size because it will influence productivity.

More People Make Lighter Work…But Only to a Point

What everyone wants to believe is if we go from 1 person to 2 people, or from 2 people to 4 people, we will get double the work done, even top managers of transnational organizations have raised this with me. But even so, we intuitively know that this is not true, but why?

In 1967, Amdahl’s Law was presented for the first time, which for those who are not systems or electronics engineers, tries to estimate how much speed gain can be obtained by executing computational tasks by running them in parallel parts. This means that sometimes there are computer programs that are viable to be worked on by multiple processors at the same time (e.g. parallel processing), but other parts must be taken care of one by one (e.g. serial programming).

The formula derived from Amdahl’s Law may seem intimidating, but it is much simpler than it seems:

If we take the 5 units of work and apply 3 processors to the parts that can be done concurrently (in parallel), it doesn’t take 1 and 2/3 units of time (5 divided by 3) to complete. Instead, 3 units are needed because 2 of the units of work can only be done by one (serial) processor. It’s certainly an improvement over time, but not as much as you’d expect at first glance.

Teamwork works in much the same way. In fact, if we convert everything to a graph we can get an idea of how efficient the increase in team members can be:

Let’s focus for now on the 80% line (the blue one, at the top) of the graph. Let’s be optimistic (and unrealistic) and assume that 80% of the work can be done by working in parallel. This suggests that the more people do it, the faster it will be over, right? Oh but wait. If we go from 1 person to 2 people, we don’t do twice as much work. To get an improvement of 2x the work completed, we actually need 3 people. 7 people only create a 3.2x improvement over 1 person. To do 4 times as much work as 1 person does, we would need 16 people!

What if even less work can be done at the same time (parallel)? What if 50% of the work needs to be done serially (green line on the graph)? Then with 9 people we still have only 1.8x speedup.

What is the solution? There is no easy solution, but there are things you can do to mitigate the effect of Amdahl’s Law:

- Make as much of the work as possible can be done in parallel. This may mean increasing cross skills and collaboration.

- Reduce dependencies between teams, so there are no bottlenecks or delays.

- Increase the speed of the overall work process by improving quality and practices.

Speed doesn’t come from sending more people to work and building bigger teams. It’s about building a high-performing team that is optimally sized for effectiveness, communication, and quality.

Research-Backed Evidence

American Sociological Association

The American Sociological Association published a study by Hackman JR, Vidmar NJ called “Effects of size and task type on group performance and member reactions”[12].

In this study, they had participants complete a series of tasks: a combination of production (writing), discussion, and problem-solving. Participants were placed into different groups of 2 to 7. After completing each task, the volunteers were asked a series of questions, including two shown in this graphic: “was your group too small?” your group was too big? As you can see from the graph, groups around 4-5 in size seemed to have the least negative reaction. The frequently touched number is 4.6. The participants were college students, the tasks were cognitively loaded but not related to technology, development, etc., and the groups were not together long enough for a true “sense of team” to form. Nevertheless, it is an interesting fact.

In those days Hackman wrote the book Leading Teams, his rule of thumb for team size was 6[13].

Social and Developmental Psychology Researcher Jennifer S. Mueller

Research psychologist Jennifer S. Mueller, academic, author, and research collaborator, was quoted in the article “Is Your Team Too Big? Too small? What is the correct number?:”

If companies are dealing with coordination tasks and motivational issues, and you ask, ‘What is your team size and what is optimal?’ that correlates to a team of six. “Above and beyond five, and you begin to see diminishing motivation,” says Mueller. “After the fifth person, you look for cliques. And the number of people who speak at any one time? That’s harder to manage in a group of five or more.”

From the Scrum Creators…nothing less

Based on studies by George A. Miller, and later work, Scrum creators Jeff Sutherland and Ken Schwaber showed the following levels of productivity creating their own research on team size:

Agile Team Productivity NO Agile Team Productivity < 7 members 300 / 400% < 7 members 100% max > 7 members 400% > 7 members < 90% And they added:

A small team from three to four people can be very autonomous when it follows guidelines, has a well-defined focus, and everyone is physically in the same space. His work is often consistent, responsible, aligned and well directed, and communication is fluid. Things are relatively easy when there are only a few people on the team. The problems seem to increase along with the number of team members.

Brook’s Law and Lawrence Putnam

The mythical Frederick Brooks to whom we owe the famous “Brooks’ Law” establishes that “adding manpower to a late software project makes it even later”. This is due to the learning curve, that is, you must train each person new to the product or technology, and you must learn all the related non-technical knowledge, including the business strategies that the product or software addresses [14].

According to important studies by renowned researchers such as Lawrence Putnam:

Miembros Esfuerzo < 9 miembros 25% menos esfuerzo > 9 miembros 25% más esfuerzo With an Agile Team:

Miembros Productividad 1 25% más 5 125% más 9 225% más In summary, if we have an optimal team, we can have productivity from 300 to 400%.

Putnam and Myers Hard Facts

Beyond our personal opinions, those of clients, bosses, and team members, we also have objective statistics. Putnam and Myers examined data from 491 software projects from a large corporation as reported in their article “Familiar Metric Management: Small is Beautiful Once Again“. These were projects with 35,000 – 90,000 lines of source code. They divided the projects into groups called buckets based on the number of people involved in the project: 1.5-3, 3-5, 5-7, 9-11, and 15-20. On average, the smaller groups (3-5, 5-7) took much less time (11.9 and 11.6 months, respectively) than the larger groups (17.1 and 16.29 months) to complete projects of similar size.

When you multiply the number of team members by the number of months, you get a graph that is even more impressive:

A team of 9 to 11 people took 2.5 to 3.5 times as long as teams of 5 to 7 and 3 to 5 to complete projects of a similar size. That suggests that the seven-plus teams in this dataset were just a way to spend money faster due to increased team size but reduced net return.

Evidence of Agile projects

Larry Maccherone, in his work through Rally, Tasktop and AgileCraft exposed in “Impact of Agile Quantified” in late 2014, has helped build large datasets on Agile team practices. His data shows:

Based on Larry’s data, it would appear that 1-3 teams are more productive but have lower quality. 3-5 teams are marginally more productive than 5-9 teams, although they may still be of slightly lower quality – the difference is small. Larry’s notes suggest that he thinks the entire range of 3 to 9 is fine [16]. The reason for the lower quality in the smaller teams is not obvious. Perhaps due to a lack of stability? Lack of diversity of thought and experience? Reduced cross-functionality? We cannot know, but it deserves consideration.

My experience

When clients, managers, etc. ask me how big Scrum teams should be, I don’t have a “correct” answer. But I try to share the above data, my personal opinions, and suggestions based on years of experience. And I won’t lie to you, there are organizations where bad habits are so ingrained that it’s hard to get that information across in a practical way (they don’t listen to it, they don’t take it into account enough, etc.). But I certainly try to make my suggestions based on evidence, simple logic, and common sense.

For example, larger teams spend more time building, more time normalizing, and therefore more time reaching high performance. Why? Because there are more relationships to negotiate. As we saw before, in a team of 5, there are 10 relationships that need to be formed, a team of 7 has 21 relationships, and so on. More relationships take more time to build and establish trust, so that should be taken into account when deciding on team size.

Assuming all else is equal (skills needed to get the job done, diversity of thought, etc.), the existing evidence supports the idea that teams of 4 to 6 work well in most situations. They take less time to train and are just as productive as larger teams. Also, teams of 5-7 can usually combine abilities enough to cover the loss of a team member.

Personally, I would only pick a team of 8 if other pressures, like the breadth of skills required, forced it to happen. I don’t recommend teams with more members, because the overhead costs outweigh the value of the additional person.

With teams of 10 or more, I recommend splitting into 2 teams. My own experience and that of other agile colleagues with scaling experience: Separate teams of 4 and 5 do more than their original large team.

With teams of 9 or more, I recommend splitting into 2 teams. My own experience mirrors that of other agilists using Scrum: separate teams of 4 and 5 do more than their original big team.

Why not 3 or less? Because it would result in very little diversity of thought and it would probably be very difficult to find 3 people with enough skills to get the job done on a complex project. There will also be very little collaboration, which correlates with the reduction in quality shown in Figure #2 (“Impact of Agile Quantified” data). And don’t forget the obvious 2v1 power issues that can make the journey more challenging for one team member.

All the focus has been on the number of people on the team, but the bigger question should be this: does the team have the ability to get to “Done” or “Done” at the end of each Sprint? If not, you’ll want to re-examine and reconfigure to achieve a more effective team size and most likely do a re-analysis to break down work into requirements, user stories, or the like.

[1] “The Impact of Lean and Agile Quantified” – Larry Maccherone showed that dedicated team members doubled productivity and stable teams (no turnover) improved productivity by 60%. https://www.infoq.com/presentations/agile-quantify

[2] Wilkinson, David. Group decision-making. What he said in The Oxford Review, Diciembre 2019

[3] “What Google Learned From Its Quest to Build the Perfect Team”: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/28/magazine/what-google-learned-from-its-quest-to-build-the-perfect-team.html

[4] “The New Science of Building Great Teams” – Alex “Sandy” Pentland https://hbr.org/2012/04/the-new-science-of-building-great-teams/ar/pr and also “Evidence for a Collective Intelligence Factor in the Performance of Human Groups“

[5] The Wisdom of Teams: Creating the High-Performance Organization – Jon Katzenbach and Douglas Smith – indicates that potential skills are as important as the skills people currently have in predicting effectiveness.

[6] [7] [8] Wilkinson, David. Group decision-making. What he said in The Oxford Review, Diciembre 2019

[9] “The Magical Mystery Four: How Is Working Memory Capacity Limited, and Why?” – Nelson Cowan – https://www.psychologicalscience.org/journals/cd/19_1_inpress/Cowan_final.pdf?q=the-recall-of-information-from-working-memory

[10] Knowledge management https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Knowledge_management

[11] These are informal observations that anyone can get, but one of the most well-known investigations was done by the English magazine Nature Human Behavior in 2017.

[12] Stable reference: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2786271

[13] Familiar Metric Management – Small is Beautiful-Once Again – Lawrence H. Putnam and Ware Myers https://hbswk.hbs.edu/archive/2996.html

[14] The Mythical Man-Month: Essays on Software Engineering – Frederick Brooks https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Mythical_Man-Month

Related links:

Agile’s Origins and Values

The Agile Team Approach

What Scrum Master Certification to Choose?

Too Big to Scale – Optimal Scrum Team Size GuideSome books to know more:

Emmanuel Herrera

IT professional with several years of experience in management and systems development with different goals within public and private sectors.

Emmanuel worked through development and management layers, transitioning from developer and team development leader to Project Manager, Project Coordinator, and eventually to Scrum Master, Product Owner, and Agile Coach.

Some certifications include: PSM, PSPO, SSM.

No CommentAdministración / Management / Administración de Proyectos / Project Management / Agile / Destacadas / Featured / ScrumMucho se ha hablado sobre el tamaño del equipo Scrum, Agile y casi cada cliente, jefe y colaborador con los que he trabajado hacen esta pregunta en algún momento ¿cuántas personas incluimos en los equipos?. La Guía Scrum ofrece muy poco luz al respecto, sugiriendo 10 o menos miembros por equipo en su última actualización, pero sin darnos contexto o razones para estos números.

El Tamaño del Equipo Scrum no es Sólo un Número

La verdad es que no existe un número universalmente correcto para asegurar un óptimo rendimiento en un equipo, pero sí sabemos que un equipo Scrum debe considerar ciertos factores que debería incluir, más allá de lo números:

- Equipo multifuncional. Habilidades y capacidades suficientes para construir el producto,

- Miembros dedicados al equipo. Miembros dedicados a uno, y sólo un, equipo,

- Miembros estables. Membresía consistente y de largo plazo dentro del equipo[1],

- Diversidad de pensamiento. Un suficientemente amplio rango de actitudes, creencias, generos y patrones de pensamiento[2].

Ahora bien, los puntos anteriores ya por sí mismos representan reto para algunas organizaciones, pero al menos gozan de un consenso importante, sin embargo, no son las únicos. Una vez que el equipo está formado, hay otros factores importantes que deben atacar los equipos de alto rendimiento, entre otros se pueden mencionar:

- Seguridad psicológica. Ambiente seguro para compartir ideas y tomar riesgos[3].

- Comunicación igualitaria. El miembro más expresivo no debería comunicar más del doble de información que el más callado[4].

- Mente abierta y disponibilidad para aprender[5].

- Visión compartida. Todos conocen y acuerdan objetivos[6].

- Roles claros. Todos conocen sus responsabilidades y las espectativas de su labor[7].

- Asesoramiento externo (coaching). En Scrum esto lo lleva a cabo el Scrum Master[8].

¿Y todo esto que tiene que ver con el tamaño de los equipos? Bueno, estos factores no viven aislados en el vacío y sólo porque yo lo digo, así que exploremos la evidencia para que juntos descubramos que es lo más importante para su equipo. Después de todo, no hay una respuesta universal 🙂

Muchos Números por Todos Lados

Cuando hablamos del tamaño de los equipos a los adentros de varias organizaciones, el tema parece mucho más controversial y poco acotado por decir lo menos. En el peor de los casos, los líderez encargados de asignación de personal responden armando equipos guiados por supuestos e incluso en función del agobio causado por fechas y presupuestos poco realistas y de horizontes inadecuados, perjudicando así al rendimiento de equipos y la misma organización a mediano y largo plazo.

En lo días tempranos del agilismo, los textos XP y Scrum sugerían que el tamaño óptimo de miembros era 7±2, aplicando el número de George A. Miller, posteriormente se ajustó a 6±3, hoy en dia el número sugeridos es 10 o menos de acuerdo con la Guía Scrum.

El sustento original para la postura de siete personas, más o menos dos (7±2), proviene de una investigación de psicología muy nombrada del psicólogo investigador George A. Miller publicada en los años 50s, donde según los resultados de este estudio, hay límites en la cantidad de información que podemos procesar y retener en nuestras cabezas.

Más recientemente en 2010, Nelson Cowan afirmó que Miller era demasiado ambicioso y que el límite ideal era solo de cuatro y no de de siete[9].

También, Ikujiro Nonaka y Hirotaka Takeuchi estaban formulando el tamaño ideal del equipo después de realizar investigaciones y crear nuevos productos en compañías de tecnología como Fuji-Xerox, Canon, Honda, Epson, Brother, 3M y Hewlett-Packard[10] .

Muchos otros citan ejemplos históricos que se remontan al ejército romano, que utilizaba pequeñas unidades militares de alrededor de 8 personas. Otros observan a los bonobos, uno de los parientes genéticos más cercanos a los humanos, a menudo divididos en grupos de 6 a 7 para buscar alimento durante un día. Ambos admiten convenientemente el número 7±2, pero dado que ninguno de los ejemplos se trata de equipos que realizan trabajo de conocimiento, la relevancia de esto para el agilismo es limitada.

Como puede ver el tema ya tiene tiempo discutiéndose y puede ser algo confuso, pero gracias a ello tenemos algunas pistas, pero vale la pena tener más fuentes que nos ayuden a sustentar nuestra desición.

¿Qué Pasa a las Relaciones Cuando los Equipos Crecen?

A los adentros de un equipo, cada individuo tendrá conexión con otro individuo creando con ello un relación única; entre más grande el equipo, más relaciones. La ecuación que describe esto es N(N-1)/2; pero ¿qué significa esto? y ¿cómo puede ayudarnos? para averiguarlo recordemos problemas de matémáticas de escuela y convirtámoslo en algo que podamos usar en la vida real.

La ecuación anterior nos dice cuántas relaciones diferentes existirán dentro de un equipo de cierto tamaño, siendo N = el número de personas en el equipo. Entonces, en el primer gráfico ejemplo de un equipo de 5 personas, donde N=5 tenemos 10 relaciones: 10 combinaciones diferentes de miembros del equipo que se relacionan con otros miembros del mismo equipo.

En el segundo ejemplo, donde N=7, tiene 21 relaciones y en donde N=9 en el tercer gráfico tienen 36 relaciones. Cada par de personas representa una relación, y esa relación define la forma en que colaboran. Los equipos de alto rendimiento, por su naturaleza, deben tener relaciones sólidas entre cada uno de los miembros del equipo para colaborar de manera efectiva.

Saber esto es importantes para usted y su equipo, porque es cierto que cada nueva persona agrega algo de productividad individual al equipo, pero también aumenta los gastos generales de comunicación en forma de un número de relaciones que crece exponencialmente. Para aumentar un equipo de 5 a 7 personas, hay que duplicar con creces el número de relaciones. Para pasar de 7 a 9, no se duplica del todo, pero el salto sigue siendo grande.

¿Qué tan costoso es mantener estas relaciones? Como anécdota, después de haber estudiado las interacciones de los miembros de varios de mis equipos, puedo decir que en equipos de 7 u 8 personas, cada día se dedican más de 90 minutos por persona a interactuar con otros miembros del equipo[11]. Esto excluye el tiempo dedicado a técnicas como pair programming. Parte de la interacción es hablar sobre el trabajo, pero también se dedica a socializar. Esto es bueno e importante porque es la combinación de trabajo y socialización lo que desarrolla la resiliencia y la capacidad de un equipo para manejar los desafíos de manera efectiva.

Una regla general sugiere que las personas suelen tener de 3½ a 5 horas de tiempo productivo en el trabajo cada día. A medida que un equipo crece, perdemos productividad o, más a menudo, comenzamos a retraernos socialmente en lugar de sacrificar tiempo productivo para interactuar con nuestros compañeros porque los costos de comunicación para cada miembro del equipo se están volviendo demasiado altos. Necesitamos relaciones sólidas para convertirnos en un equipo de alto rendimiento pero, a medida que crece el tamaño del grupo, comenzamos a evitar las interacciones que construyen esas relaciones.

Por lo tanto, la cantidad de relaciones entre los miembros del equipo y la inversión de tiempo que requieren deben ser un factor considerado al elegir el tamaño del equipo porque influirá en la productividad.

Más Personas Hacen el Trabajo Más Ligero… Pero Solo Hasta Cierto Punto

Lo que todos quieren creer es que si vamos de 1 persona a 2 personas, o de 2 personas a 4 personas, obtendremos el doble de trabajo realizado, incluso altos directivos de organizaciones transnacionales me lo han planteado. Pero incluso así, intuitivamente sabemos que esto no es verdad, pero ¿por qué?

En 1967 se presentó por primera vez la Ley de Amdahl, que para los que no sean ingenieros en sistemas o electrónica, trata de estimar cuanta ganancia de velocidad se puede obtener ejecutando tareas de computo corriédolas en partes de manera paralela. Esto significa que a veces hay programas de cómputo que son viables de trabajarse por múltiples procesadores al mismo tiempo (ej. procesamiento paralelo), pero otras partes deben ser atendidas una por una (ej. programación serial).

La fórmula que se deriva de la Ley de Amdahl pude parecer intimidante, pero es mucho más simple de lo que parece:

Esta imagen plantea trabajo realizado por un procesador el cual le toma 5 unidades de tiempo para completar.

Si tomamos las 5 unidades de trabajo y aplicamos 3 procesadores a las partes que se pueden hacer concurrentemente (en paralelo), no se necesitan 1 y 2/3 unidades de tiempo (5 dividido por 3) para completarse. En cambio, se necesitan 3 unidades porque 2 de las unidades de trabajo solo pueden ser realizadas por un procesador (serie). Ciertamente es una mejora en el tiempo, pero no tanto como cabría esperar al primer vistazo.

El trabajo en equipos funciona de manera muy similar. De hecho, si con convertimos todo a un gráfico podemos darnos idea de que tan eficiente puede ser el incremento en miembros de un equipo:

Enfoquémonos por ahora en la línea del 80% (la azul, en la parte superior) del gráfico. Seamos optimistas (y poco realistas) y supongamos que el 80% del trabajo se puede hacer trabajando en paralelo. Esto sugiere que cuanta más gente lo haga, más rápido se terminará, ¿cierto? Ah, pero espera. Si pasamos de 1 persona a 2 personas, no hacemos el doble de trabajo. Para obtener una mejora de 2 veces el trabajo completado, en realidad necesitamos 3 personas. 7 personas sólo crean una mejora de 3.2 veces sobre 1 persona. Para hacer 4 veces más trabajo del que hace 1 persona, ¡necesitaríamos 16 personas!

¿Qué sucede si se puede hacer incluso menos trabajo al mismo tiempo (paralelo)? ¿Qué pasa si el 50% del trabajo debe hacerse en serie (línea verde en el gráfico)? Luego, con 9 personas, todavía tenemos solo una aceleración de 1.8 veces.

¿Cual es la solución? No hay una solución fácil, pero hay cosas que puede hacer para mitigar el efecto de la Ley de Amdahl:

- Haga que la mayor parte del trabajo posible se pueda hacer en paralelo. Esto puede significar aumentar las habilidades cruzadas y la colaboración.

- Reduzca las dependencias entre equipos, para que no haya cuellos de botella ni retrasos.

- Aumente la velocidad del proceso de trabajo en general mejorando la calidad y las prácticas.

La velocidad no proviene de enviar a más personas al trabajo y formar equipos más grandes. Se trata de construir un equipo de alto rendimiento que tenga un tamaño óptimo para la eficacia, la comunicación y la calidad.

Evidencia respaldada por investigaciones

American Sociological Association

La American Sociological Association publicó un estudio de Hackman JR, Vidmar NJ llamado “Effects of size and task type on group performance and member reactions.” algó así como “Efectos del tamaño y el tipo de tarea en el desempeño del grupo y las reacciones de sus miembros“[12].

En este estudio, hicieron que los participantes completaran una serie de tareas: una combinación de producción (escritura), discusión y resolución de problemas. Los participantes se colocaron en diferentes grupos de 2 a 7. Después de completar cada tarea, se les hizo una serie de preguntas a los voluntarios, incluidas dos que se muestran en este gráfico: “¿su grupo era demasiado pequeño?”, “¿su grupo era demasiado grande?”. Como puede ver en el gráfico, los grupos de alrededor de 4-5 de tamaño parecían tener la reacción menos negativa. El número frecuentemente tocado es 4.6. Los participantes eran estudiantes universitarios, las tareas tenían una carga cognitiva pero no estaban relacionadas con tennología, desarrollo, etc., y los grupos no estuvieron juntos el tiempo suficiente para que se formara un verdadero “sentido de equipo”. No obstante, es un dato interesante.

Por aquellos días Hackman escribió el libro Leading Teams, su regla general para el tamaño del equipo era 6[13].

Social and Developmental Psychology Researcher Jennifer S. Mueller

La Psicóloga-Invetigadora Jennifer S. Mueller académica, autora y colaboradora de varias investigaciones fue citada en el artículo “Is Your Team Too Big? Too Small? What’s the Right Number?:”

Si las empresas están lidiando con tareas de coordinación y problemas de motivación, y usted pregunta: “¿Cuál es el tamaño de su equipo y cuál es el óptimo?”, eso corresponde a un equipo de seis. “Más allá de los cinco, comienzas a ver una disminución de la motivación”, dice Mueller. “Después de la quinta persona, buscas camarillas. ¿Y el número de personas que hablan en un momento dado? Eso es más difícil de manejar en un grupo de cinco o más”.

De Los creadores de Scrum…ni más ni menos

A partir de los estudios de George A. Miller, y trabajos posteriores, lo creadores de Scrum Jeff Sutherland y Ken Schwaber mostraron los siguientes niveles de productividad basados en su propia investigación sobre el tamaño del equipo:

Equipo Agile Productividad Equipo NO Agile Productividad < 7 miembros 300 / 400 % < 7 miembros 100% max > 7 miembros 400 % > 7 miembros < 90% Y agregaron:

Un pequeño equipo de tres a cuatro personas puede ser muy autónomo cuando sigue pautas, tiene un enfoque bien definido, y todos están físicamente en el mismo espacio. Su trabajo es a menudo consistente, responsable, alineado y bien dirigido, y la comunicación es fluida. Las cosas son relativamente fáciles cuando solo hay unas pocas personas en el equipo. Los problemas parecen aumentar junto con el número de miembros del equipo.

Ley de Brooks y Lawrence Putnam

El mítico Frederick Brooks al cual se le debe la famosa “La Ley de Brooks” establece que “agregar mano de obra a un proyecto de software tardío lo hace incluso más tardío”. Esto es debido a la curva de aprendezaje, es decir, debe capacitar a cada persona nueva en el producto o tecnología, y debe aprender todo el conocimiento no técnico relacionado, incluidas las estrategias comerciales que aborda el producto o el software [14].

Según importantes estudios realizados por investigadores de renombre como Lawrence Putnam:

Miembros Esfuerzo < 9 miembros 25% menos esfuerzo > 9 miembros 25% más esfuerzo Con un Equipo Agile:

Miembros Productividad 1 25% más 5 125% más 9 225% más En resumen, si tenemos un equipo óptimo, podemos llegar a tener una productividad del 300 al 400%.

Datos duros de Putman y Mayers

Más allá de nuestras opiniones personales, las de los clientes, jefes, miembros del equipo, también tenemos estadísticas objetivas. Putnam y Myers examinaron datos de 491 proyectos de software en una gran corporación como publicaron en su aritículo “Familiar Metric Management: Small is Beautiful Once Again“. Estos fueron proyectos con 35,000 – 90,000 líneas fuente de código. Dividieron los proyectos en grupos que llamaron buckets según la cantidad de personas involucradas en el proyecto: 1.5-3, 3-5, 5-7, 9-11 y 15-20. En promedio, los grupos más pequeños (3-5, 5-7) tardaron mucho menos tiempo (11.9 y 11.6 meses, respectivamente) que los grupos más grandes (17.1 y 16.29 meses) para completar proyectos de tamaño similar.

Cuando multiplicas el número de miembros del equipo por el número de meses, obtienes un gráfico que es aún más impactante:

Un equipo de 9 a 11 personas tardó entre 2.5 y 3.5 veces más tiempo que los equipos de 5 a 7 y de 3 a 5 para completar proyectos de un tamaño similar. Eso sugiere que los equipos de más de siete en este conjunto de datos eran solo una forma de gastar dinero más rápido debido al aumento del tamaño del equipo pero con rendimiento neto reducido.

Evidencia de proyectos Agile

Larry Maccherone, en su trabajo a través de Rally, Tasktop y AgileCraft expuestos en “Impact of Agile Quantified” a finales del 2014″, ha ayudado a construir grandes conjuntos de datos sobre prácticas en equipos Agile . Sus datos muestran:

Enlarge

Relacion Tamaño-Rendimiento Maccherone Según los datos de Larry, parecería que los equipos de 1-3 son más productivos pero tienen menor calidad. Los equipos de 3-5 son marginalmente más productivos que los de 5-9, aunque aún pueden tener una calidad ligeramente inferior: la diferencia es pequeña. Las notas de Larry sugieren que piensa que todo el rango de 3 a 9 está bien[16]. La razón de la menor calidad en los equipos más pequeños no es evidente. ¿Quizás por falta de estabilidad? ¿Falta de diversidad de pensamiento y experiencia? ¿Funcionalidad cruzada reducida? No podemos saberlo, pero merece consideración.

Mi Experiencia

Cuando los clientes, jefes, etc., me preguntan qué tamaño deberían tener los equipos Scrum, no tengo una respuesta “correcta”. Pero trato de compartir los datos anteriores, mis opiniones personales y sugerencias basadas en años de experiencia. Y no les mentiré, hay organizaciones donde los malos hábitos está tan arraigados que cuesta trabajo permear de manera práctica esa información (no la escuchan, lo toman suficientemente en cuenta, etc.). Pero sin lugar a dudas procuro que mis sugerencia se basen en la evidencia, en la lógica simple y el sentido común.

Por ejemplo, los equipos más grandes pasan más tiempo formándose, más tiempo normalizándose y, por lo tanto, más tiempo para alcanzar un alto rendimiento. ¿Por qué? Porque hay más relaciones que negociar. Como vimos antes, en un equipo de 5, hay 10 relaciones que deben formarse, un equipo de 7 tiene 21 relaciones, y así sucesivamente. Más relaciones toman más tiempo para construir y establecer la confianza, por lo que debe tenerse en cuenta a la hora de decidir el tamaño del equipo.

Suponiendo que todo lo demás sea igual (las habilidades necesarias para realizar el trabajo, la diversidad de pensamiento, etc.), la evidencia existente respalda la idea de que los equipos de 4 a 6 funcionan bien en la mayoría de las situaciones. Toman menos tiempo para formarse y son tan productivos como los equipos más grandes. Además, los equipos de 5-7 normalmente pueden combinar habilidades lo suficiente como para cubrir la pérdida de un miembro del equipo.

Personalmente, solo elegiría un equipo de 8 si otras presiones, como la amplitud de habilidades requerida, lo obligaran a suceder. No recomiendo equipos de más miembros, porque los gastos generales superan el valor de la persona adicional.

Con equipos de 10 o más, recomiendo dividirse en 2 equipos. Mi propia experiencia y la de otros colegas agilistas con experiencia en escalamiento: los equipos separados de 4 y 5 hacen más que su numeroso equipo original.

Con equipos de 9 o más, recomiendo dividirse en 2 equipos. Mi propia experiencia refleja la de otros agilistas utilizando Scrum: los equipos separados de 4 y 5 hacen más que su gran equipo original.

¿Por qué no 3 o menos? Porque daría como resultado muy poca diversidad de pensamiento y probablemente sería muy difícil encontrar 3 personas con suficientes habilidades para hacer el trabajo en un proyecto complejo. También habrá muy poca colaboración, lo que se correlaciona con la reducción en la calidad que muestra la Figura n.º 2 (datos de “Impact of Agile Quantified”). Y no olvide los problemas obvios de energía 2 contra 1 que pueden hacer que el viaje sea más desafiante para un miembro del equipo.

Todo el enfoque se ha centrado en la cantidad de personas en el equipo, pero la pregunta más importante debería ser esta: ¿tiene el equipo la capacidad de llegar a “Done” o “Terminado” al final de cada Sprint? Si no es así, querrá volver a examinar y reconfigurar para lograr un tamaño de equipo más efectivo y hacer muy probablemente un re-análisis al desglose de trabajo en requerimientos, historias de usario o similares.

[1] “The Impact of Lean and Agile Quantified” – Larry Maccherone demostró que miembros dedicados a un sólo equipo duplicaron la productividad y los equipos estables (sin rotación) mejoraron la productividad en un 60%. https://www.infoq.com/presentations/agile-quantify

[2] Wilkinson, David. Group decision-making. Lo que dice la última investigación. The Oxford Review, Diciembre 2019

[3] “What Google Learned From Its Quest to Build the Perfect Team”: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/28/magazine/what-google-learned-from-its-quest-to-build-the-perfect-team.html

[4] “The New Science of Building Great Teams” – Alex “Sandy” Pentland https://hbr.org/2012/04/the-new-science-of-building-great-teams/ar/pr y también “Evidence for a Collective Intelligence Factor in the Performance of Human Groups“

[5] The Wisdom of Teams: Creating the High-Performance Organization – Jon Katzenbach and Douglas Smith – indica que las habilidades potenciales son tan importantes como las habilidades que la gente tiene actualmente para predecir efectividad.

[6] [7] [8] Wilkinson, David. Group decision-making. Lo que dice la última investigación, The Oxford Review, Diciembre 2019

[9] “The Magical Mystery Four: How Is Working Memory Capacity Limited, and Why?” – Nelson Cowan – https://www.psychologicalscience.org/journals/cd/19_1_inpress/Cowan_final.pdf?q=the-recall-of-information-from-working-memory

[10] Knowledge management https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Knowledge_management

[11] Estas son observaciones informales que cualquiera puede hacer, pero una de las investigaciones más conocidas la hizo la revista inglesa Nature Human Behavior en 2017.

[12] Stable reference: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2786271

[13] Familiar Metric Management – Small is Beautiful-Once Again – Lawrence H. Putnam y Ware Myers https://hbswk.hbs.edu/archive/2996.html

[14] The Mythical Man-Month: Essays on Software Engineering – Frederick Brooks https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Mythical_Man-Month

Enlaces de interés:

El Enfoque Agile De La Planeacion

Planeación, Cono de Incertidumbre y Estimaciones en IT

¿Qué Certificación Elegir como Scrum MasterEstos son alguno libros recomendables para saber más:

Emmanuel Herrera

IT professional with several years of experience in management and systems development with different goals within public and private sectors.

Emmanuel worked through development and management layers, transitioning from developer and team development leader to Project Manager, Project Coordinator, and eventually to Scrum Master, Product Owner, and Agile Coach.

Some certifications include: PSM, PSPO, SSM.

2 CommentsFirst of All

If you don’t know the four Agile Value Statements, I invite you to take a look at Agile’s origins and values post before continuing, if you already did or already know these values, now you can focus your attention on how the agile team approach actually is in the field. Together, the Agile Value Statements add up to a highly iterative and incremental process and deliver tested code at the end of each iteration. The next points, in general, include the overall way I which an agile team carries the project:

- Works as one

- Works in short iterations

- Release something every iteration

- Focuses on business priorities

- Inspects and adapts

The Agile team works as one

Unfortunately, is usual to see some business and systems analysts throw processes or requirements to designers and programmers like a ball over the wall and just continuing with their lives, also there are designers and architects who elaborate their appealing designs without the slightest consultation to their programmer coworkers, or talented programmer who finish their assigned part of the system and then shake their hands and disappear; and we can go on with sad stories. A successful agile team must have a “we’re in this together” mindset.

I really like using video games analogies, because are a great way to illustrate what happens in real life. A lot of online games are team games, where each member of the team has a role. In this teams, there are roles such as the healer who heals his teammates, the tank who receives hits becoming in a shield for the rest of team who can attack more efficiently, the DPS who do damage to the enemy and the special class who does some kind of damage. When a player doesn’t perform their role properly, puts the rest of the team at a considerable disadvantage, sometimes this breaks the whole team completely. Everybody must work as one!

Just like happens in this games, the agile teams also have roles, and it’s worth identifying them in a general way:

Product Owner

The main responsibilities of the product owner include making sure that the whole team shares the same vision about the project, establishing priorities in a way that the functionalities that contribute the most value to the business are always in which the team is working on. Take decisions that take the best return on investment of the project is the highest priority.

Customer

The customer is the person who made the decision to finance the project, usually represents a group or division. In these cases, it is common for this role to be combined with the product owner. In other projects, the customer can be a user.

Developer

In the context of agile teams, a developer title is used in a wide way, this is a developer can be a programmer, a graphic designer, a database engineer, user experience experts, architects, etc.

Project manager

We have to take this carefully because an agile project manager focuses more on leadership than traditional management. In some projects and agile frameworks, this figure doesn’t even exist or if it does, the person in charge of this role shares the traditional project management responsibilities with other roles such as product owner. Also can be an advisor on the adoption and understanding of the agile approach. In very small projects can even have a role as a developer, but this practice is not recommended.

The Agile team works in short iterations

Already mentioned this in previous posts, in agile projects, there is not a phase delineation too marked. There are not an exhaustive establishment of requirements at the beginning of the project followed by an analysis, there is not architectural design phase for the entire project. Once the project really starts, all the work (analysis, coding design, testing, etc.) occurs together within an iteration.

The iterations are done within a previously delimited time-space (timeboxed). This means that each iteration is completed is the agreed time without excuses, even if the planned functionalities are not finished. The iterations are often very short. Most agile teams use iterations between one week and four weeks.

The Agile team release something every iteration

Something crucial in each iteration is that within its space of time one or more requirements are transformed into codified, tested and potentially packageable software. In reality, this does not mean that something is delivered to the end users, but it must be possible to do so. The iterations one by one add up the construction of only some functionalities, in this way an incremental development is obtained by going from one iteration to the next.

Because a single iteration usually does not provide enough time to develop all the functionalities that the customer wants, the concept of release was created. A release comprises one or more (almost always more) iterations. Releases can occur in a variety of intervals, but it’s common for releases to last between 2 and 6 months. At the end of a release, this can be followed by another release and this one can be followed by another, and so on until the project is finished.

The Agile team focuses on business priorities

Agile teams demonstrate a commitment to business priorities in two ways. First, they deliver functionalities in the order specified by the product owner, which is expected to prioritize and combine features in a release that optimizes the return on investment for the project organization. To achieve this, a plan is created for the release based on the capabilities of the team and a prioritized list of the new desired functionalities. For the product owner to have greater flexibility in prioritization, the features must be written down minimizing the technical dependencies between them.

Secondly, agile teams focus on completing and delivering functionalities valued by the user instead of completing isolated tasks.

The Agile team inspects and adapts

It is always good to create a plan, but the plan created at the beginning does not guarantee what will happen in the future. In fact, a plan is just a guess at a point in time. If you live persecuted by Murphy’s Law like me 😀, there will be many things that will conspire against the plan. Project staff can come or go, technologies will work better or worse than expected, users will change their minds, competitors can force us to respond differently or faster, and so on. Agile teams see that each change represents both, an opportunity and the need to update the plan to improve and reflect the reality of the current situation.

At the beginning of each new iteration, an agile team incorporates all the new knowledge obtained in the previous iteration and adapts accordingly. If a team learned something that is likely to affect the accuracy or value of the plan, the plan must be updated. That is, perhaps the team discovered that they have overestimated or underestimated their ability to progress (capacity) and that a certain type of work consumes more time than previously thought.

In the same way, the plan can be affected by the knowledge that the product owner has gained from the users. Perhaps because of the feedback obtained from a previous iteration the product owner has learned that users want to see more of some kind of functionality and no longer value so much that they had considered. This type of situation can alter the plan, so you have to adapt it to improve its value.

Sorry about my English I’m not a natural speaker (don’t be grumpy, help me to improve).

This is all for now folks, I hope this can be useful for you.

Related links:

Agile’s origins and values

Roles on Agile Teams: From Small to Large Teams

What Is Agile?These are some recommended books to know more:

Emmanuel Herrera

IT professional with several years of experience in management and systems development with different goals within public and private sectors.

Emmanuel worked through development and management layers, transitioning from developer and team development leader to Project Manager, Project Coordinator, and eventually to Scrum Master, Product Owner, and Agile Coach.

Some certifications include: PSM, PSPO, SSM.

No Comment

Winds of Change

Much is heard about Agile, Agile project management or the “Agile methodology” as something from the 21st century, but actually, the origin and Agile values began to take shape a little earlier. The 90s were a very interesting decade, MTV had its best moment, the Grunge music invaded the radio and the Internet came to the life of the masses. Along with the Internet boom, the way of making software changed completely, companies began to learn how to create software on a large scale and for interconnected users all over the world, which brought new demands. In the search for success, many of these companies began to import “good practices” from other industries expecting good results, which in the end were mixed in many cases (see Waterfall Model).

Many electromechanical systems were already beginning to be replaced by electronic systems, and sometime later the software began to have more and more relevance, but the development and interaction of these elements were trapped in predictive models that tried to know all elements involved in a system of beforehand, which were (and still are) very difficult to establish at the beginning of software projects with high levels of uncertainty, which has since caused very long development periods with hard-to-predict end dates. This situation led to the frustration of many leaders, who despite the situation were creating and adapting their own techniques, methods, and frameworks to the traditional models of development, which eventually gave rise to the first winks of Agile thinking.

Agile is born

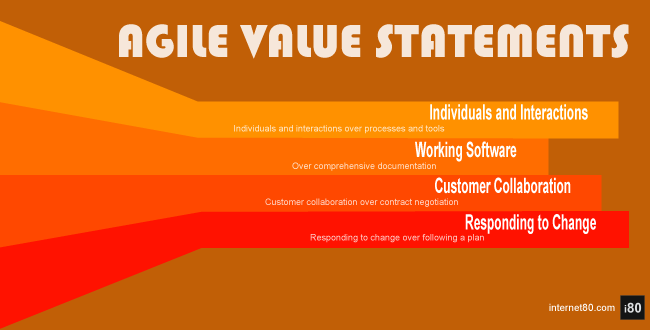

After several previous meetings, in February of 2001, a group of professionals had a new and now famous meeting whose main contribution was The Agile Manifesto. This manifesto was written and signed by seventeen software development leaders (now known as the Agile Community). Their document gave a name to how this group was developing software and provided a list of Agile value statements:

- Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

- Working software over comprehensive documentation

- Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

- Responding to change over following a plan

And this group added:That is, while there is value in the items on the right, we value the items on the left more.

You can know more about history and the original manifesto at agilemanifesto.org

In particular, these opinion leaders looked for ways to quickly build functional software and put it in the hands of end users. This quick delivery approach provided a couple of important benefits. First, it allowed users to get some of the business benefits of the new software faster. Second, it allowed the software team to obtain quick feedback on the scope and direction of software projects on a regular basis. In other words, the Agile approach was born.

Behind the Agile Value Statements

You already know the list of value statements, but let’s see what are the reasons behind them:

Value people and interactions over processes and tools. Those of us who have a path in the development world know that a team with great people works well even using mediocre tools also these teams always overcome other dysfunctional teams with mediocre people who have excellent tools and processes. If people are treated as disposable pieces there will be no process, tool or methodology capable of saving their projects from failing. Good development processes recognize the strengths (and weaknesses) of individuals and take advantage of it instead of trying to make everyone homogeneous.

Value software that works over the comprehensive documentation. Because it leads us to have incrementally improved versions of the product at the end of each iteration. This allows us to collect early and often, some feedback about the product, and the process allows us to know if we should correct the course of action, make adjustments or move forward with the same vision. As the developed software grows with each iteration, it can be shown to the probable or real users. All this facilitates the relationship with customers and improves the chances of success.

Value the collaboration with the customers over contracts negotiation. Because in order to create Agile teams we must seek that all parties involved in the project work to achieve the same set of goals. Contract negotiation sometimes conflicts with the development team and the customer from the beginning. I think the multiplayer online battle arena games are a great example, personally, I like games like Heroes of the Storm o League of Legends. These are cooperative games where teams with five members are formed, the objective is that the team must destroy the base of the enemy by working together. All players win, or all players lose. These matches are surprisingly fun, and what we would like, for software development teams and customers, is to come together with this same attitude of collaboration and shared goals. Yes, contracts are often necessary, but the terms and details of a contract can exert a great negative influence on the different parties involved, and turn a collaborative environment into an inner competitive one.

Value responding to change over following a plan. Because the main objective is to provide the greatest possible amount of value to the project’s customers and users. In large and/or complex projects, you will find that it is very difficult even for users and/or customers, to know every detail of each feature they want. It is inevitable that users come with new ideas, or that they decide that some critical features initially are no longer so. For an Agile team, a plan is a vision of the future, but many points of view are possible and environmental factors can change over the time. As a team gains knowledge and experience about a project, the plan should be updated accordingly.

With the four Agile Values Statements from the Agile Manifesto in mind, I think you can begin to understand what it means to have an Agile approach to estimating and planning.

Sorry about my English I’m not a natural speaker (don’t be grumpy, help me to improve 🙂 ).

Related links:

To agility and beyond: The history—and legacy—of agile development

What Scrum Master Certification to Choose?

These are some books to know more:

Emmanuel Herrera

IT professional with several years of experience in management and systems development with different goals within public and private sectors.

Emmanuel worked through development and management layers, transitioning from developer and team development leader to Project Manager, Project Coordinator, and eventually to Scrum Master, Product Owner, and Agile Coach.

Some certifications include: PSM, PSPO, SSM.

No CommentAdministración / Management / Administración de Proyectos / Project Management / Agile / Cursos / Courses / IT / Scrum

Aquí está el cuarto video del curso gratuito en video de Introducción a la Administración de Proyectos desde cero. Esta vez se abordarán los cinco grupo de procesos de la administración de proyectos de acuerdo al Project Manament Institute o PMI. En mi opinión el PMI en su Project Management Body of Knowledge o PMBOK es donde mejor engloban los procesos generales y las áres de conocimiento requeridas para la gestión de proyectos; independientemente de metodologías, técnicas o herramientas.

En el video se explica brevemente la relación entre los cinco grupo de procesos de la administración de proyecto y las preguntas que nos planteamos en el video Definición de Gestión de Proyectos. Los temas tratados en el video son:

- Inicio

- Planeación

- Ejecución

- Monitoreo y Control

- Cierre

Todos los videos previos están disponibles en YouTube o si prefiere, en los siguientes enlaces:

- Definición de Proyecto (Video)

- Definición de Gestión de Proyectos

- Lo Necesario Para Ser Un Administrador de Proyectos

Estos videos forman parte del primer capítulo del curso Explorando La Administracion De Proyectos. La estructura del curso puede verla aquí, la cual estaré actualizando con los enlaces apropiados según suba los respectivos videos.

El mundo de YouTube vive de vistas, likes y suscripciones (un fastidio pero así es ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ ) por lo tanto agradeceré sus manitas arriba, shares, suscripciones y todo eso que los youtubers siempre piden. También puede ver todos los videos en Patreon ahí las almas voluntariosas puede ayudar a la causa 🙂 y además pueden obtener:

- Video descargable en alta definición.

- Transcripción del contenido.

- Documentos y preguntas de práctica (sólo los videos que lo ameriten).

Como parte de Introducción a la Administración de Proyectos, del Capítulo 1 Explorando la Administración de Proyectos tenemos este cuarto video:

Algunas publicaciones recomendables para saber más:

Emmanuel Herrera

IT professional with several years of experience in management and systems development with different goals within public and private sectors.

Emmanuel worked through development and management layers, transitioning from developer and team development leader to Project Manager, Project Coordinator, and eventually to Scrum Master, Product Owner, and Agile Coach.

Some certifications include: PSM, PSPO, SSM.

No CommentAdministración / Management / Administración de Proyectos / Project Management / Agile / Cursos / Courses / IT / Scrum

Ahora tenemos el tercer video del curso gratuito en video de Introducción a la Administración de Proyectos desde cero. En esta oportunidad veremos lo necesario para ser un administrador de proyecto o project manager, veremos cuál es el perfil general que este rol require para hacer una adecuada gestión de proyectos, habilidades como:

- Habilidades técnicas

- Comprensión del negocio

- Habilidades interpersonales

- Liderazgo

El primer y segundo video están disponibles en YouTube o si prefiere, en los siguientes enlaces:

- Definición de Proyecto (Video)

- Definición de Gestión de Proyectos

- Los Cinco Procesos De La Administración De Proyectos

El mundo de YouTube vive de vistas, likes y suscripciones (un fastidio pero así es ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ ) por lo tanto agradeceré sus manitas arriba, shares y todo eso que los youtubers siempre piden. También puede ver todos los videos en Patreon ahí las almas voluntariosas puede ayudar a la causa y además pueden obtener:

- Video descargable en alta definición.

- Transcripción del contenido.

- Documentos y preguntas de práctica (sólo los videos que lo ameriten).

La estructura del curso puede verla aquí, estoy actualizando esta estructura según avanzo en la misma.